In the New World, tobacco was both thought of as a panacea for all that could ail you and as a spiritual conduit. Using it cured you, kept you safe, and gave you visions. And it also helped with what was more common in those days: a less reliable food supply.

In other words, more people were more hungry more of the time.

Tobacco, and the nicotine it contained, was an effective appetite suppressant and a food substitute. When you smoked, it both distracted you from thinking about food as well as suppressing the cravings.

Historically it appears that many psychoactive substances were adopted precisely because they helped alleviate hunger.

Hallucinations were much more common in those days. Tobacco had a much higher nicotine content, – both because of the use of tobacco (which had a much higher nicotine content) and many other suppressants with similar side effects, and because extreme hunger caused people to eat almost anything to fill their stomachs and quite often those substances had side effects.

Choosing nicotine over food

In a time when people buy, rather than grow, tobacco, there is often a choice between nicotine and food. And for some people, a smoke wins out over a meal.

I first noticed this when I lived in Indonesia in the early 2000s, where people short of money would often choose to buy cigarettes over a meal.

Nowadays, I know families in my home town who are short of money but still smoke. Sometimes the fridge is empty, but cigarettes are still bought.

Still, the research on this is limited. One small study in Australia by Murphy et al did find that a group of 20 smokers on a low income would often choose to smoke instead of eat. Smokers also reported that the stress of dealing with a lack of money lead to increased smoking, with one stating:

“If you’ve got no money and you’ve got no milk, you stress out. So you buy smokes”.

Another 2016 study by Murphy et al found that smoking decreased as food prices increased, suggesting that smokers will prioritise food over cigarettes. However, this study relied on a hypothetical scenario – asking smokers what they would do if they had a limited amount of money to spend on food or cigarettes. There’s a big difference between imagining what you would do and what you actually do when you are addicted to something.

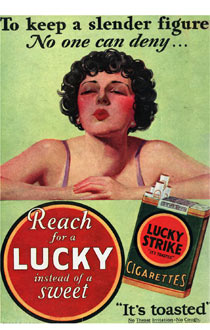

Of course, in times and places of abundance, some people deliberately use nicotine to distract them from high calories foods. In the 1920s this behaviour was very much encouraged by cigarette company American Tobacco.

Using the catchphrase ‘Reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet’ advertising campaign, the campaign successfully targeted women who were concerned about their weight. The company was eventually forced to stop making weight-related claims, but the association was already made. The number of women smokers went on to increase from 6% in 1924 to 48% in 1944.

How does nicotine reduce appetite?

Choosing nicotine over food is not always a deliberate choice, and sometimes comes down to how our brain interacts with nicotine.

For example, a 2011 study by Mineur et al found that when a nicotine receptor, α3β4, was activated, it decreased appetite amongst mice, with body fat dropping from 20% to 15% over 30 days. (A couple of caveats – first, of course, this was an animal study, and secondly, it only looked at male mice.)

Another study by Meineur et al conducted in 2011 (itself sparked by the unexpected findings of the previous 2011 study) found that nicotine sparks the same receptors in brains that are involved in our ‘flight or fight’ response.

When we are in a flight or fight response, we are geared towards survival – and our appetite is suppressed because it’s less important than the immediate danger.

A second possibility is linked to an element that makes smoking addictive. (A common misunderstanding is that nicotine is the only addictive element in cigarette smoke – in fact, there are other elements such as cotinine that likely contribute towards the addiction.)

When you smoke, or anticipate smoking, the brain releases dopamine – which creates the feeling of anticipation or pleasure. Smokers get used to a regular release of dopamine, and experience cravings when they do not experience this.

A 2011 study by Rubinstein et al suggests that as smokers get used to this regular use of dopamine, natural reinforcers of dopamine such as food become less powerful:

“…even at low levels of nicotine exposure, brain regions linked to reward have decreased responses to pleasurable food images compared with nonsmokers.”

Does vaping help you lose weight?

All of this is a problem. While the average weight gain of 5 -10 pounds after quitting smoking is less harmful than smoking, it can still deter people who value a slim waistline from quitting.

Quitting smoking is always the best answer, even if it involves some weight gain. But for people who can’t or won’t quit nicotine, it’s best to use it in its safer forms – one of which is vaping.

Theoretically, as vaping contains nicotine, it should also help control weight. Some people also become more active when they switch from smoking to vaping, which could also help control weight.

On the other hand, as ex-smokers/new vapers regain their taste buds, food starts to taste better. What’s more, if you are using very sweet e-liquids, your taste may change, making food taste less sweet, and leading you to crave more.

Still, this is conjecture only, and there’s not yet enough good research to be sure that vaping can lead to weight loss. However, if you do vape, it’s probably best to avoid sweet e-liquids if you can.